RICHMOND BARTHE

HARLEM RENAISSANCE SCULPTOR

|

|

|

|

|

- Traveling Exhibition -

Curator:

Samella Lewis, Ph.D.

Professor Emerita, Art History

Scripps College, Claremont, CA

- Barthe Short Bio - Exhibition Info - Illustrated List of Works - Schedule

- Installation Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, TN -

- Installation Museum of African American Art, Los Angeles, CA -

- Intro to Book - Preface by Elizabeth Catlett - Public Works Images -

- Contact Information - Exhibition Website -

_______________________________________

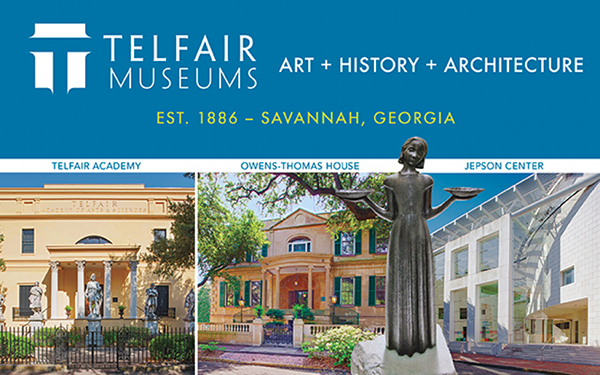

Exhibition To Be Presented at the

Telfair Museums, Savannah, GA

August 4 - November 5, 2023

Link to Telfair Museums

|

|

|

|

|

|

Richmond Barthé (1901-1989) is recognized as one of the foremost sculptors of his generation. Following his graduation from The Art Institute of Chicago in 1928, Barthé moved to New York and established a studio in Harlem where he became associated with the Harlem Renaissance. He is also known for his many public works. This exhibition is curated by esteemed art historian, Samella Lewis, Ph.D., in conjunction with the publication of her extensive biography Barthé, His Life In Art. Included in the exhibition are 25 sculptures plus photomurals of Barthe and his public works.

|

|

|

|

|

RICHMOND BARTHE

(1901-1989)

A Short Biography

by Samella Lewis

|

|

|

|

Richmond Barthe and Samella Lewis

Richmond Barthe (1901-1989) was a man who endured and triumphed as he followed his own star, a star that led him to many parts of the world in search of opportunities to express the creative vision that marked his presence in this life and, according to Barthe, preceding lives.

Barthe often referred to himself as an "Old Soul" who had been here before. In discussing his belief in reincarnation, he insisted that during an earlier life he was an artist who lived in Egypt. He believed that he was an artist in each of his earlier lives and that he would always be an artist. How else would it have been possible for him to accumulate the experiences and skills that he displayed in his more recently completed life?

A review of Barthe's enormously successful career as a sculptor causes one to wonder how, with such limited training in the field, he was able to reach such heights as to rank among America's top sculptors of his time.

Born in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, to Richmond Barthe and Marie Clementine Roboteau, Barthe never knew his father who died at the age of twenty-two when Richmond was only one month old. This left his mother, who played a significant role in his life, with the responsibility of rearing her son alone.

An early influence in her son's artistic development, Barthe's mother, he recalled, often gave him his favorite toys—a marking pencil and paper—to entertain him during her busy periods while she worked. "Mother used to leave me at home when she went out to work. That was when I was a baby. She would put me on the floor with a piece of paper and a crayon, drawing and scribbling."

As a child he was fascinated with shapes, especially those of fancy Old English letters that he saw in the headlines of the New Orleans Times Picayune. He also liked comic strip characters. Later, Barthe began drawing people he saw on the streets. He and his mother played games in which they decided to name the people and animals and insects that he drew. Barthe continued this practice and personalized just about everything, including birds, bees and chickens.

Barthe continued to demonstrate a remarkable talent and, at the age of twelve, his work was shown at the County Fair in Mississippi. By the time he reached the age of eighteen, Barthe, now residing in New Orleans, won his first prize— a blue ribbon for a drawing he sent to the County Fair. His work attracted the attention of Lyle Saxon, the literary critic (who was also interested in art) of the New Orleans Times Picayune. Saxon tried, unsuccessfully, to register Barthe in a New Orleans art school. The refusal was based on Barthe's race, rather than a lack of creative ability, thus making Barthe more determined than ever to follow his own star and become a famous artist.

With the aid of a Catholic priest, the Reverend Harry Kane, S.S.I., Barthe, with less than a high school education and no formal training in art, was admitted to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1924. During his four-year stay at the Institute he pursued a career as a painter. Father Kane could only provide for tuition. Consequently, this left Barthe with the challenging task of feeding himself and buying art supplies. He embarked on a grueling work schedule. Fortunately, he was able to live with an aunt who agreed to provide free housing for him during his stay in Chicago.

During the last year of his study at the Art Institute, Barthe's anatomy teacher, Charles Schroeder, suggested that in order to gain a better understanding of the third dimension in his painting, Barthe should try modeling in clay. Using two of his classmates as models, he followed his teacher's advice and sculpted two heads. "A fellow student had a beautiful head. I wanted to get it in three dimensions instead of the single dimension of painting, so I asked him if I could model his head. I have always done sculpture since then." Barthe did not discard the works, which he liked very much, but instead decided to exhibit them in the newly-organized Negro History Week Exhibition. Barthe executed busts of artist Henry 0. Tanner and Haitian General Toussaint L'Ouverture which were exhibited at a children's home in Gary, Indiana. These two works, along with those exhibited during the Negro History Week Exhibition, were included in the April 1928 annual exhibition of the Chicago Art League. A response to Barthe's work during this period appeared in an article by William H. A. Moore, published in the November 1928 issue of Opportunity Magazine:

Richmond Barthe is an artist of unusual powers. He has come to us at a time when we are sadly in need of a real inspiration, of that spiritual food that heartens and strengthens, in hopes that embody the willingness to do the larger and truer things of life. There is the magic of earnestness in his work. There is the charm of unassertive measure of beauty which stamps the work of all true artists. Different from Rodin, apart from Epstein, his work somehow partakes of the realization of artistic aim which distinguishes the work of each of these masters.

These events proved to be turning points in Barthe's career. In addition to his sculpture being admired by the critics, he received numerous commissions to do portrait busts.

In February, 1929, following his graduation from The Art Institute of Chicago, Barthe moved to New York where he began to rise to stardom as a sculptor. During the next two decades he would build a reputation that would prove to be the envy of many of his peers. The 1930s and 1940s would see him rise to greater prominence. No other sculptor in the United States during this period received higher praise for his work by critics or more visibility in the New York press.

Barthe established his first studio in New York in Harlem. He began to fraternize with writers, dancers and theater personalities soon after he arrived. His reputation as a sculptor was generally known in Harlem and was acclaimed by philosopher/art critic Alain Locke, who praised his sculpture and regarded it as fresh and vibrant.

By his industrious application Barthe had developed a seasoned technical proficiency: thirty-seven subjects in five media ranging from portrait commissions to heroic figure compositions, like "Mother and Son," and the forty foot has reliefs of "Exodus" and "Dance" for the Harlem Housing Project, attest to his original talent and steadily maturing artistic stature. Critics, both conservative and modernist, agreed in their praise of his work because of his undeniable proficiency and versatility. This adaptation of style to subject is Barthe's forte. Always seeking a basic and characteristic rhythm and a pose with a sense of suspended motion, there is an almost uncanny emphasis, even in his heads, on symbolic line, like the sinuous patterned curves of his dancing figures, the sagging bulbous bulk of the "Stevedore," or the lilting flow of "Feral Benga," the sophisticated African dancer. During his first year in New York, Barthe completed approximately thirty-five sculptures. By 1934, his reputation was so well established that he was awarded his first solo show at the Caz Delbo Galleries in New York City. His exhibitions and commissions were numerous. Additions to permanent collections, such as the Whitney Museum—"African Dancer," "Blackberry Woman," and "Comedian," and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—"The Boxer"—seemed commonplace. Commissions included a bas relief of Arthur Brisbane for Central Park, and a commission for a huge 8' x 80' frieze of "Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho," for the Harlem River Housing Project.

As Barthe's commissions of theater personalities increased, he decided to move his studio from Harlem to a larger, more comfortable space downtown. This move prompted some controversy and rumors suggesting that Barthe had little or no time for his own race.

Barthe's response to this charge was, "That is decidedly untrue. I am definitely quite interested in my own race and quite proud to be a Negro. I merely live downtown because it is much more convenient for my contacts from whom it is possible for me to make a living."

As early as 1938, Richmond Barthe had a burning desire to visit Africa: "I'd really like to devote all my time to Negro subjects, and I plan shortly to spend a year and a half in Africa studying types, making sketches and models which I hope to finish off in Paris for a show there, and later in London and New York."

Although Barthe's stated reason for moving downtown was his need to be accessible to his clients, another reason was that he loved the theater and wanted to be in the company of the stars of the "legitimate" theater. In spite of the com-missions-and grants, he was not always able to afford the price of tickets to most performances because a major portion of his funds was spent on producing works of African and African American people which, in many cases, were not sold. Living downtown made Barthe more available for invitations and free tickets to theater and dance performances.

Richmond Barthe did not believe that race should determine what an artist should produce. He did, however, feel that his race was an advantage in his rise to fame.

Being a Negro has been a help rather than a hindrance to me. In the Chicago Art Institute, my work was always noticed because I was the one Negro in that particular section. I'm sure there were other students doing better work at the time who were not noticed. Art is not racial. For me there is no Negro art—only art. I have not limited myself to Negro subjects. It makes no difference in my approach to the subject matter whether I am to model a Scandinavian or an African Dancer. For instance, I selected a young Negro as my model for the marble head, "Jimmie," because of his particularly engaging smile. If he had been white and had the same smile, I'd have chosen him just as readily.

His good looks, hard work and natural talent made an unbeatable combination. He stood out in the downtown crowd, and his humble personality set him apart from other more aggressive personalities.

In New York Barthe experienced success after success. He was considered by writers and critics as one of the leading "moderns" of his time. The busy, tense environment in which he found himself took its toll, and he decided to abandon his life of fame at the peak of his career and move to Jamaica, West Indies. Barthe remained in Jamaica for twenty productive years. Away from the limelight he was in a place that, although distant from his beloved Bay St. Louis, reminded him of the place of his childhood. There he could commune with nature and experience the beauty of the land.

Almost forgotten in New York art circles, his reputation flourished in Jamaica. He remained there until the mid-1960s when the rampant violence that Barthe had left in Manhattan began to occur in Jamaica. Armed gangs were roving neighborhoods, spraying bullets into homes, killing innocent inhabitants. Barthe decided, again, that he would not live in an environment where he could not function freely without fear of mental and/or physical intimidation.

Richmond Barthe spent the next five years of his life in Switzerland, Spain and Italy before settling in Pasadena, California. During his last years he thought of returning to painting but instead worked on his memoirs and resumed his communication with his friends in nature— the birds, bees and other living creatures that he could trust.

The significance of the art and life of Richmond Barthe established a chapter in the history of art in America. His poise, dignity, intelligence, and esthetic sensibility are reflected in the timeless monuments that he has left for our enjoyment and appreciation. These monuments, Barthe's sculptures, are from the heart, mind and spirit of a man who endured and who triumphed as he followed his own star.

|

chmond Barthe and Samella Lewis

RICHMOND BARTHE

HIS LIFE IN ART

Introduction to Book

By Samella Lewis

It can be said that the young are impressionable and that, over time, the cultural and sociopolitical contexts in which they live and work include all that will influence them and all that they will assimilate and transform. This sentiment rings ever true as one follows the life of and studies the body of work by the sculptor James Richmond Barthe. During my first discovery of Barthe, the "impressionable" aspect of the sentiment was never more evident.

It was 1944. I was a student majoring in art and general studies at Hampton Institute (now named Hampton University). One day, while reading the arts section of The New York Times, I noticed a sculpture by Barthe that had been included in an exhibition in honor of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. This work—The Negro Looks Forward (1944)—was one of the most passionate and inspiring pieces that I had ever seen. Later referred to as The Negro Looks Ahead, it became one of the nation's, and one of Barthe's, most celebrated sculptures.

While still a student, I imagined being the owner of this intuitively created sculpture. Determined to discover more about the artist and his work, I began a study of his life and art. I learned a great deal: that Barthe was among the acclaimed sculptors in the United States during the 1930s and 1940s; that critics regarded his work as modernistic; and that such museums as the Whitney Museum of American Art, the preeminent contemporary art museum in the United States, collected his work early in his career. Yet, my investigation raised many questions that I believed only the artist himself could answer. It would be slightly more than thirty years before I had the opportunity to speak with him in person.

A friend, actor-director Ivan Dixon, introduced me to Barthe soon after the latter's arrival in Pasadena, California, in 1976. During my interviews with the sculptor, he commented on several topics, including art, race and reincarnation. In regard to race, his beliefs remained unchanged throughout his life.

Being a Negro has been a help rather than a hindrance to me. In the Chicago Art Institute, my work was always noticed because I was the one Negro in that particular section. I'm sure there were other students doing better work at the time who were not noticed.

It is likely that this perspective was based, in part, on the experiences that he had as a child and as a young adult. He spent his childhood in a relatively isolated community, Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, and escaped some of the hazards of growing up Black and male in Mississippi during that time. Some negative factors existed, of course, but overall, positive personal experiences prevailed. The people of color in Bay St. Louis formed a closely knit community and responded to each other's needs. Although an absolute division existed between the races in the community, it was widely known that Jimmy, as he was called as a child, wanted to be an artist, and people of all races contributed what they could to help him to attain his goal. Barthe believed that artists should explore how something feels rather than how it looks. If he felt something inwardly, he said, his hands took care of themselves, so he didn't have to make a conscious effort executing it.

Man is like a light bulb. It can only get light through the little wire that connects it directly with the power plant. So it has to go within itself for light. Man, like the light bulb, is connected to the universal mind, cosmic consciousness or God— whatever you want to call it—and the only way he can get help or inspiration is by going within himself and drawing on this power. This is where artists, poets, composers and scientists get their ideas and inspiration. It is the source of all knowledge. You just have to go within, relax and let it flow through you.

Barthe's art was therefore a reflection of how he felt about whom and what he was studying. All his life, the artist said, he had been interested in studying people. He loved people—people of all races, creeds and economic levels. In exploring both their basic nature and their manifestation of that essence, he always tried to capture the spiritual quality inherent in them. He said, "My work is not based on surfaces or stylization but on what is inside of it. I'm not interested in style, medium or subject matter."

In Barthe's sculptures, we are aware of his passion and vigor, which exceed the boundaries of his figures. An examination of The Boxer (1942), Inner Music (1956) and Julius (1942) will attest to his ability to bridge the gap between realism and abstract form. Although the artist's sculptures on the surface appear to be traditional figurative forms, upon closer examination, many works are expressionistic, with elongated and uniquely distorted characteristics.

Barthe saw himself as an intuitive dreamer. His vision extended beyond the material to spiritual values that incorporated the nature of societies and how people functioned within them. A believer in reincarnation, the artist often referred to himself as an old soul. He insisted that he had lived as an artist in many parts of the world during his "earlier lives" and that he would always be an artist. He also believed what a medium had told him: In his previous lives, Barthe had lived in Greece, Egypt and Atlantis and had gone back to Atlantis in his dreams. The turquoise, clear ocean of Jamaica, where he lived for nearly twenty years, reminded him of the color of the ocean he had seen in his dreams, in which he was strolling through the water underneath the surface of the sea. Barthe said that his work The Seeker (1965) is based on his experience in that dream.

During my visits with him, our conversations made me feel as though we were old friends busy "catching up" and sharing ideas. As Barthe talked with his hands, feet, and body, I also learned that he had followed his own path, one that led him to many parts of the world in search of opportunities to express the creative vision that marked his presence in this life and, according to him, in previous lives. These opportunities, as well as his personal growth and development and his experiences and relationships, are noted and discussed in the following pages. In addition, I have also included some of his fables, which the artist entrusted with me, because they shed light on his psychological disposition and his moral fiber.

He devoted much of his oeuvre to themes regarding religion, race, the theater and portraiture. The illustrations in this book represent his magnificent body of work. A sculptor for more than sixty years, Barthe dedicated his life to art, creating timeless treasures in which his poise, dignity, intelligence and aesthetic sensibility are reflected. I would be remiss if I failed to mention his persistent tendency to use the male nude as an object of beauty. The only Black sculptor of his generation for whom the male nude was essential, Barthe executed sensual figures during an era when Black men were considered a sexual menace. His daring and successful use of the nude mirrors the spirit of a man who followed his own star.

To imagine Barthe's qualities as a sculptor, one would therefore have to invent a fine artist with the deftness of Langston Hughes, the sensuousness of Michelangelo and the boldness reminiscent of Charlie Parker. With these qualities in mind, one wonders how, with such limited training in the field of sculpture, Barthe was able to accumulate the experience and skills to rank among the finest contemporary sculptors of his time.

His work in general has universal appeal. Thus, it can easily seduce anyone who responds to sculpture, in and for itself, as I found that memorable day at Hampton. I shall never forget it. And I hope that this review of the life and art of Richmond Barthe will help past and future generations not to forget him, for his work constitutes a significant chapter in the history of art in the United States of America and the world.

Samella Lewis

January 2008

__________________________________________________________________________________________

RICHMOND BARTHE:

HIS LIFE IN ART

Preface to Book

by Elizabeth Catlett

When focusing on the art of James Richmond Barthe, this book rediscovers the works of a neglected, creative genius. Many museums in the United States and abroad honored him during his lifetime, as did colleges and universities, U.S. presidents, mayors, art institutions and the like. Yet, the sculptor's reputation diminished as an artist after his relocation to the Caribbean island of Jamaica and to Europe for twenty-seven years. Moreover, the contemporary art world has continued its disregard for the passion, energy and courage inherent in this gifted man's work of art:.

I first met Barthe in the late 1940s in New York City. I was in the process of maturing as an artist, and he had earned critical acclaim as a major sculptor. When I met. him in 1982 in Pasadena, California, it appeared as if time had warmly embraced him. We talked about our lives and our perspectives on art. I told him that I loved his sculpture African Dancer, and he informed me that, it is in the permanent collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art. While conversing with him, I also found it interesting that neither he nor I used models. I am proud to say that all of his sculptures—figurative forms, portraits and nudes—are distinguished by their extraordinary beauty, depth and stellar quality.

This book is a revelation in many ways. The most important, I believe, is the firm yet tender commitment of Samella Lewis to this project. Before his death in 1989, she promised Barthe that she would write and publish a comprehensive tome on his life in art. This book is a testament to that promise. She conceived it. She executed it. She worked hand in hand with Shirley Poole, her editor, who was diligent and meticulous during both the editorial and the production process. And, because of all these factors, Samella has ensured that this book is a superb cultural presentation.

Art lives beyond the years, the decades, the centuries, as we know it. As such, it conveys a tradition that influences artists, different forms of expression and art institutions. As one reads and views the sculptures in this book, it is evident that James Richmond Barthe worked toward the embodiment of a tradition that enabled him to depict the core of those whom he studied and modeled. This book is verification that his body of work has stood the test of time.

Elizabeth Catlett

January 2008

___________________________________________________________________________________________

|

Exhibition Info

Dates Avail: 2023

- 2026

Contents: 25 bronze sculptures, photo murals

Publication: Book

Space Req: 1,500 - 2,500 sq feet.

Loan Fee: Price on request

Insurance: Exhibitor responsible

Shipping: Exhibitor responsible

Req: Appropriate security - vitirnes for smaller works

Contact: info@a-r-t.com 310-397-3098

________________________________________________________________________________

Schedule

as of 03/15/23

2009

September 1 - Dec 31

Museum of African American Art, Los Angeles, CA

2010

Oct 3 - January 2, 2011

Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, TN

2011

February 4 - April 17

NCCU Art Museum, Durham, NC

October 7 - January 15, 2012

Sheldon Memorial Art Galllery, Lincoln, NE

2012

July 13 - September 15

The August Wilson Center, Pittsburgh, PA

2023

August 4 - November 5

Telfair Museums, Savannah, GA

December 1-31

OPEN

2024-2026

OPEN

____________________________________________________________________

- Barthe Short Bio - Exhibition Info - Illustrated List of Works - Schedule

- Installation Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, TN -

- Installation Museum of African American Art, Los Angeles, CA -

- Intro to Book - Preface by Elizabeth Catlett - Public Works Images -

- Contact Information - Exhibition Website -

|

|

|

|

|